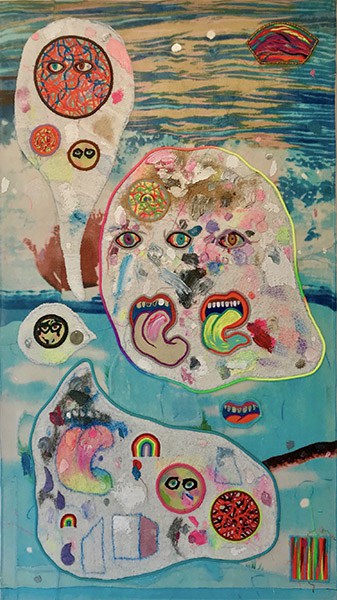

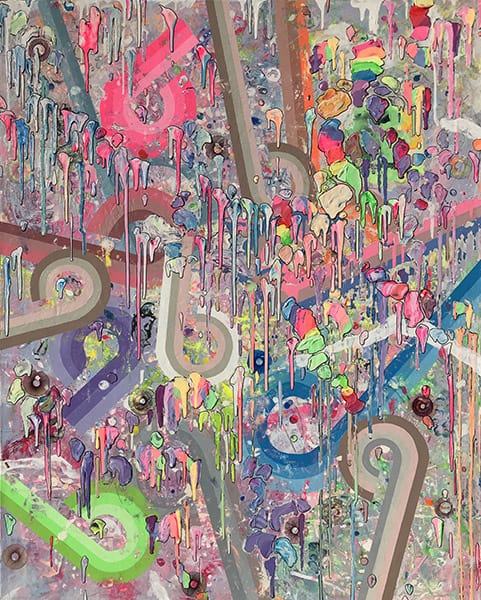

The Past/Next One Hundred Years, 2019

Acrylic, gel medium, ink, pencil, colored pencil, digitally altered and defaced laser prints and paper on canvas

Carter is the first artist within our collection that we would like to honor as this pandemic continues to shut galleries and cancel exhibitions. His solo show “Didn’t We Almost Have It All” at the Anglim Gilbert Gallery could not be a more accurate title in light of recent events, as the gallery announced on the 14th of March the temporary closure of the venue in order to protect the safety and health of many of their visitors, artists and staff.

Carter last had an individual show in 2017 and now, 3 years later, he continues his explorations of identity, visibility and sexuality alongside the dynamic representations of the artist’s mixed media pieces. The Adrastus Collection reached out to Carter to discuss his latest exhibition and the progression of his work and practice, which he tells us, took him almost two years to complete.

Adrastus Collection (AC): Since your last exhibition, we see more connection with color and physical body parts emerging from the canvas, could you discuss the developments between the two exhibitions?

Carter: Color has moved to the forefront in the new works over the past few years.

The strong use of color is not just a tool but has become a study and creation of different ‘color palettes’ that for me reference certain years, social movements and particular moments in time. The new dominant use of color has been an interesting situation as it has run rampant – almost like wrestling a tiger by the tail and not caring if it bites you.

AC: Interested in reproduction and the way objects can substitute human presence and eventually act in the place of other objects, in particular in times of isolation, how has it had an impact on your work? Now that isolation has become mainstream, how does it gain new perspective on the subject?

C: Isolation becoming mainstream, (due to the COVID-019 Virus) has affected us all. Artists for the most part, myself included, are isolated most of the time when they are working.

For me, isolation in the studio has always been a blessing and a curse; isolation for days, weeks and months when working on an exhibition is a luxury, but there are moments that isolation can turn slightly toxic. The worldwide isolation that this virus has created is not at all a luxury when it comes to working in the studio. It’s nearly impossible to shift gears and work on a painting when you’re bombarded by daily death counts. This new isolation will of course pass, but for now, it’s easier and perhaps time is better spent watering my plants, reading and watching television. The long lineage and language of painting that I’ve created in the studio will return at some point, and that language will organically change as it always has.

AC: Your work is now available online to view on Artsy, how do you believe the digital format will impact the interaction audiences will have with your work?

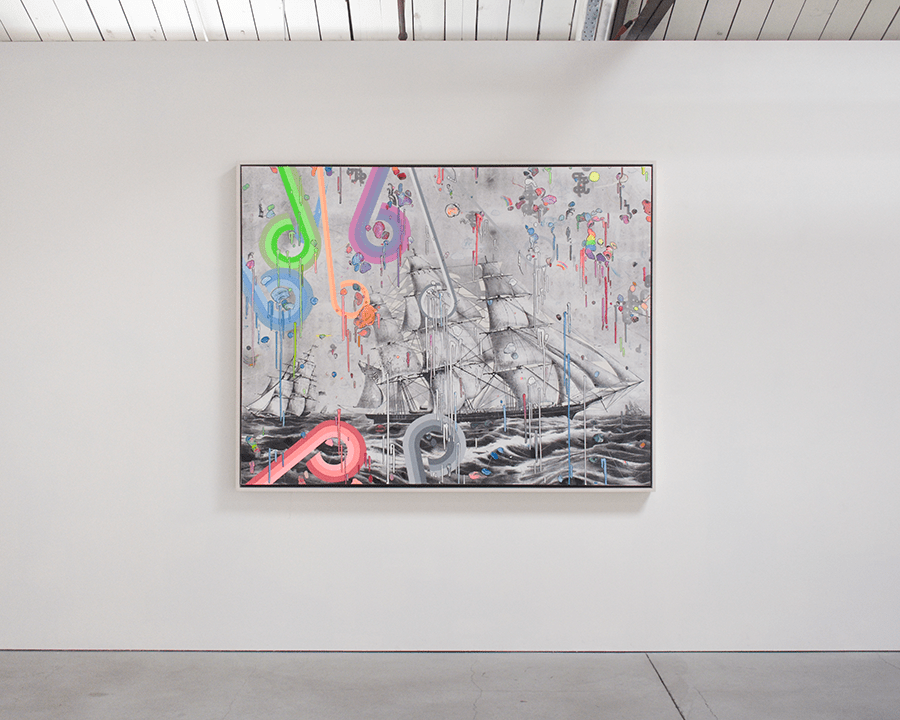

C: In March I was in San Francisco for an opening of new paintings I had been working on for close to two years. 13 paintings. The exhibition was open for a couple weeks and then closed prematurely because of the virus. The gallery (Anglim Gilbert Gallery) have placed the work online. Having a 72 x 56 inch painting be presented solely in a digital format is disappointing and does a disservice to the details and spirit of the work, but it is the world we live in and often the only way to present work to a broader audience. Galleries having to close their physical spaces is truly sad for everyone involved; the artists, their work, and the owners and employees of the galleries. Having paintings that are vibrant and yearn to communicate, sit alone on gallery walls that have been shuttered is sad all around. Having said that – there’s something conceptually sweet about artwork that are active, being sequestered and placed on pause.

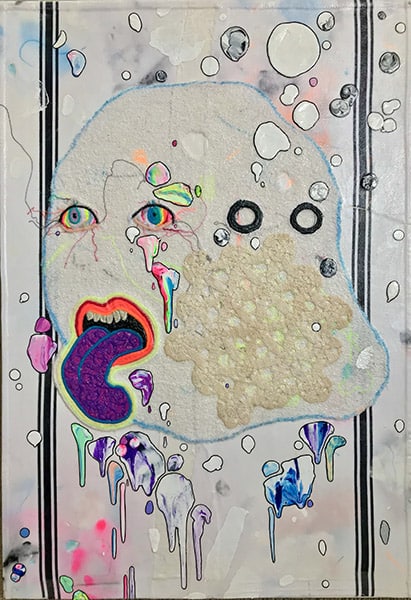

“Didn’t We Almost Have It All”, 2019/2020

Acrylic, gel medium, ink, colored pencil and

paper on canvas

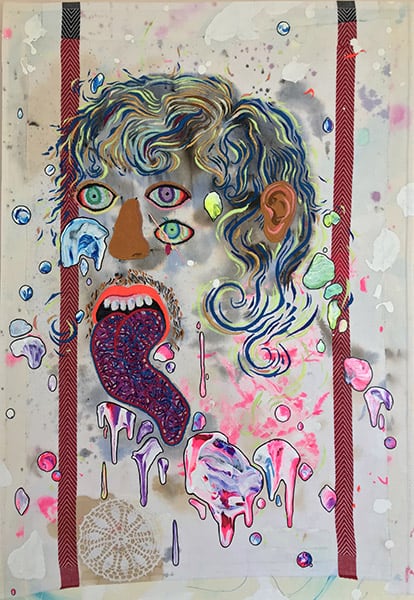

“Emote/Display”, 2019/2020

Acrylic, gel medium, ink and paper on canvas

A not-so-subtle shift from his previous work, the pieces Carter presents for the 2020 exhibition features gobs of paint and permutations of color seamlessly protruding from the artworks in various shapes and forms. Setting out the peregrination through its traces on the canvas, these representative flags point out, “Carter’s subtle variations of the same forms, his abject and non-descript shapes converge as a catalogue of physical possibilities,” as mentioned in the Adrastus Collection’s previous critical essay from his exhibition in 2015.

Carter’s search for identity and sexuality has been named as an undercurrent in many of his previous works, however this time he touches on the theme of sexuality in a more aggressive fashion, describing it himself as, “wrestling a tiger by the tail and not caring if it bites you”. He extenuates this by making deliberate flagging’s of color in the illustrative use of the LGBT community flag in its bright neon colors in his works. However, this technique strikes an almost satire tune. Thirty years ago, Gerhard Richter painted commercial color charts to satirize the inflated claims then being made for abstract art. Therefore this almost overly blatant use of neon colors that Carter has omitted, could seek to add humor to those trying to seek out his identity.

Much like the designers of the aesthetic of the late 1960s counterculture, Carter uses bubble lettering, and collage effects that create an optical illusionistic art, better known as ‘op art’. Drawing from the abstract painters Bridget Riley and Josef Albers, one can see the play with color and effect taking place in the work and color used as if it was almost a political act. In 1970, “the hippies” were awarded the Sikkens prize, a Dutch award for groundbreaking work in the use of color (other recipients have included Riley and Dutch designer and architect Gerrit Rietveld).[1]

Carter’s hallucinatory palette is tempered by the incorporation of coffee-stained terrycloth, tea towels, and other embellishments linking himself to other artistic movements such as to Dada and Duchamp, “artists interested in destruction as much as creation, of making something new out of taking things apart,” says Josh Siegel, associate curator of film at MoMA, who invited Carter to show his film Erased (2009) at the museum.[2] This only invites us to delve more deeply into the mysterious unconsciousness of the overtly colorful and deeply reflective work of Carter, as he steps into this next stage of his evolution as an artist.

All images courtesy of Anglim Gilbert Gallery.

[1] Hoggard, Liz. “The Revolutionary Artists of the 60s’ Colourful Counterculture.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 4 Sept. 2016, www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/sep/04/revolutionary-artists-60s-counterculture-v-and-a-you-say-you-want-a-revolution.

[2] TheAdvocateMag. “In a Word: Carter.” ADVOCATE, Advocate.com, 6 Apr. 2009, www.advocate.com/arts-entertainment/film/2009/04/06/word-carter.