Herbert Hamak: The Judd Influence

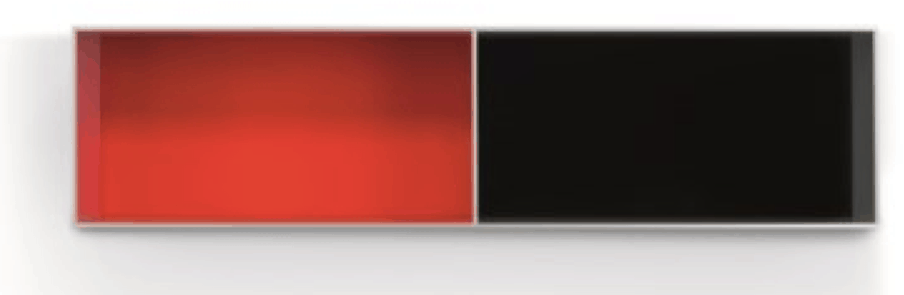

Untitled (H159N), 2000

Pigment and binding agent on linen

Starting in the early 1960’s, the Minimalist period was characterized by unitary objects with geometric forms and patterns, in which industrial materials were often incorporated, blurring the boundaries between painting and sculpture. The movement, born from the Abstract Expressionism, attempted to avoid metaphorical associations and symbolism. From Dan Flavin to Carl Andre, the minimalist style evolved to include a number of divergent artistic variants. Over half a century later, minimalism still holds a strong influence in contemporaneity. This can be identified in the relation between Herbert Hamak and Donald, as both artists sought autonomy and clarity for the constructed object and the space created by it through their artworks. The idea behind both men’s work has become a driving force of influence, as Herbert continued Judd’s legacy by creating similar spaces.

With the intention of creating work that could assume a direct material and physical ‘presence’, he disdained from teachings of classical ideals of representational sculpture. Donald Judd has also famously said, “Everything sculpture has, my work doesn’t,”[1] whose visual vocabulary sought clear and definite objects, with an increased importance of installation as his primary mode of articulation. The Italian philosopher and art critic Luciano Anceschi has written previously,

“Once a work of art has passed from the artists’ hand it is present, in front of the viewer or listener, with all its shapes and colours, all its images in sound, its tones and pitches. And in its expression it completely resolves both itself and what it contains. It seems to need nothing, to be happy in its self-sufficiency, to have arrived at calm and stillness. And yet its life has only just begun. In the meanwhile it reclines in silence until it is recognized and accepted. Its meaning finds nothing to refer to and the work is as though closed in expectant isolation. Its symbols seem silenced, its language new and incredible.”[2]

Anceschi talks about the sense of alienation that artworks create and the sculptures that both Hamak and Judd are able to achieve, while at the same time raising the vital point that an artwork can just be, and does not need explanation. This is emphasised even more by the blank titles that both artist chose to give to their work. In Adrastus Collection’s artwork Untitled (H159N) (2000), the most notable factor is that it doesn’t ‘express’ something.

Donald Judd, Untitled(1987)

This possibility of the physical and emotional allusions is created between the calibrating relationship of colours and transparencies. Hamak has a very specific way of working with his sculptures, as he mixes paint pigments into a binding agent made of artificial resin and wax and then he pours it into a mould. Stretching the traditional canvas over wood, before the substance becomes solid, one will be able to visualise the colour towards the end of the process. Using different media, the artist creates both opaque and transparent visual bodies, which can appear to glow in natural light.[3] His work incorporates the intensified colour of painting, focusing on its purity and diffused through a resin-filtered light in the sculpture but also embodies the three-dimensionality space of a sculpture. In Untitled (H159N) (2000), the intense colour of red and black stand out, visually and physically as the majority of Hamak’s sculptures are positioned on walls or standing structures. Much like Donald Judd’s Untitled (1987), it too stands as a last innovation of the artist’s signature sculptural form of the stack. For the Menziken series Judd used Swiss-manufactured aluminum, achieving a matte-even look and one that reflects light with a subtle elegance. However Judd chose to repeat these engineered rectangular containers to compose Untitled (Menziken 88-16), which became fundamental to the artist’s oeuvre.[4]

Much like Hamak, the technique in which Donald Judd made his impeccable anodized silver structures was unique. The material of aluminum contrasts to the cadmium red on the right side of the boxes and to the deep black acrylic sheet on the left. Donald Judd believed that red articulated the edges, angles and textures of his incisive forms and sculptures and can therefore be understood as a motive behind Hamak’s choice as well.

The symbolic meaning of red and black was important for several reasons, from the Maya codices to the contemporary colours of artists Josef Albers and Barbara Kruger[5], Judd envisaged the marriage of red and black to result in a specific visual experience: “In a way, side-by-side, the red and the black become one color. They become a two-color monochrome. Red and black together are so familiar that they almost form a new unity.”[6]

Donald Judd, Untitled (Menziken 88-16), (1988)

Thus, Hamak’s choice of colour and structure of the object was deliberately trying to follow the ideals of Donald Judd. Allowing both Hamak’s sculptures and The Menziken boxes of Judd to capture both artists’ relentless experimentation with new materials, color combinations, scale and form. Both providing quintessential examples of Hamak and Judd’s thoroughly innovative aesthetic.

Herbert Hamak was born in 1952 in Unterfranken. He lives and works in Hammelburg, Germany. He has exhibited in some of the most important museums and galleries in Italy and abroad. Among these are the following solo shows, including the latest: A Matéria da Cor at Galeria Raquel Arnaud, São Paulo (2017); Herbert Hamak – “At the end of the rainbow” at Studio la Città, Milan (2017); Galerie Hollenbach at viennacontemporary (2016); L’insostenibile leggerezza del colore, Perlartecontemporanea, Lugano (2015); Point Alpha, con testo di/with text by Marco Meneguzzo, Studio la Città, Verona (2015); Galerie Tanit, Munich (2013); A Bunch of Roses, Studio la Città, Verona (2013); Galerie Xippas, Paris (2013); Galería Xavier Fiol, Palma de Mallorca (2011); Museum Haus Lange, Krefeld, curated by Martin Hentschel (2010); Geukens & de Vil, Knokke (2009); Galleria Traghetto, Venice (2009); Anima ed Esattezza, 2000 & Novecento, Reggio Emilia (2009); Studio la Città, Verona (2008); Sebastian Guinnes Gallery, Dublin (2008); Archiginnasio, Bologna (2008); Oltre, Galleria Civica G. Segantini, Arco (2007); Ultramarinblau Dunkel Pb 29.77007, Museo di Castelvecchio, Verona (2007); Galerie Christian Roellin, St. Gallen, Switzerland (2006); Geukens & De Vil Contemporary Art, Knokke-Zoute, Belgium (2006); Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice (2006); Galerie Xippas, Paris (2005); Studio Visconti, Milan (2005); Kunsthalle Mannheim, Mannheim (2005); Kenji Taki Gallery, Tokyo and Nagoya (2005).

[1] Kosuth, Joseph. “Histories and Theories of Intermedia.” Art After Philosophy (1969), Joseph Kosuth. N.p., 01 Jan. 1970. Web. 24 Apr. 2017. <http://umintermediai501.blogspot.com/2008/10/art-after-philosophy-1969-joseph-kosuth.html>.

[2] Luciano Anceschi. Progetto di una sistematica dell’arte (Translated from the Italian). Mursia; Prima Edizivne. 1962.

[3] Luca Massimo Barbero, and Martin Hentschel. Herbert Hamak. Kerber, 2010.

[4] “Donald Judd – Untitled (Menziken 88-16).” Phillips, Phillips, www.phillips.com/detail/DONALD-JUDD/NY010716/19.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Donald Judd, “Some Aspects of Color in General and Red and Black in Particular,” 1993, in Colorist, Ostfildern, 2000, p. 79