Dancing once again with Nietzsche through Oscar Santillan’s installation Afterword

Afterword (2015)

Oscar Santillan

Installation including a piece of paper belonging to Friedrich Nietzsche, a slide projection, two prints, and a video projection.

A slide projection composed by fourteen slides, a piece of paper, two prints and a video projection, integrate Oscar Santillan’s installation Afterword (2015). Inspired by the unexplored territory where fact and fiction converge, Oscar Santillan fulfills the deepest desires from the German philosopher Nietzsche, into a contemporaneous reality.

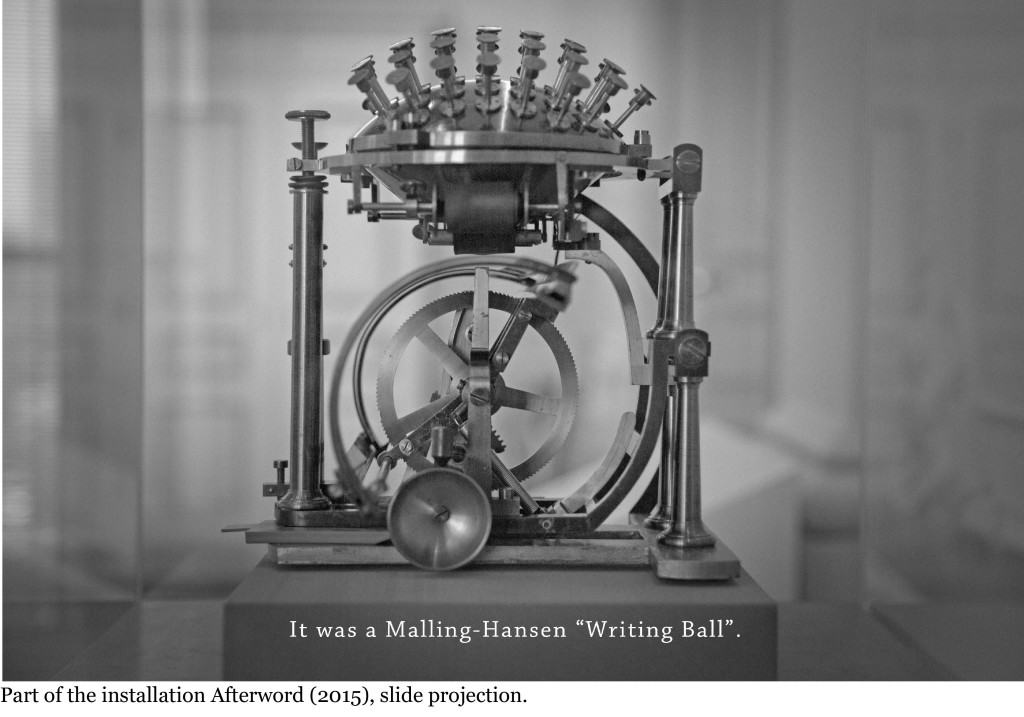

Due to his messy handwriting and sight complications, the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche acquired a typewriter in 1881 with the intention to continue his writing. In fact, he ordered a cutting-edge device developed by the Danish inventor Rasmus Malling-Hansen called “Writing Ball”. Invented in 1865 and put into production in 1870, the “Writing Ball” was the first commercially produced typewriter, introducing an unusual design and ergonomic innovations. Its distinctive feature was the arrangement of the 52 keys placed on a large brass hemisphere in order to allow the fastest writing speed.

Unfortunately, Nietzsche wasn’t totally satisfied with his purchase and never really mastered the use of the instrument. By his own, Nietzsche spent hours teaching his fingers “to dance with the Malling-Hansen”. He clamed that his thoughts were influenced by his use of a typewriter and even wrote of dancing himself “as if something supernatural” echoed out of him in his text Our writing instruments contribute to our thoughts (1882). In this document, Nietzsche is among the firsts to notice a change in the writing style and how the writing instruments contribute to our thoughts. He was so intrigued by this machine, that he even wrote a poem:

“The writing ball is a thing like me, made of iron,

Yet easily twisted on journeys.

Patience and tact are required in abundance,

As well as fine fingers to use us.”

(English translation

Friedrich Nietzsche, on February 16th 1882)

Recent research by Rüdiger Safranski founded that the machine was damaged during its transportation and produced a lot of typing mistakes. Despite his frustrations, Nietzsche typed more than 70 documents using it. Some of them were abandoned and many others were corrected and finalized with increasingly agitated pencil marks over the errors.

Fascinated by the frustrations of one of the world’s greatest philosophers, the Ecuadorian visual artist, Oscar Santillan produced an installation depicting Nietzsche’s experience of the typewriter which framed his understanding of language in a highly symbolic way: the traditions of the philosophy of language versus the scientific and technological conditions of knowledge. The result is an expressive and gestural document accompanied by a compilation on a single page of all of the errors that Nietzsche made using his beloved “Malling-Hansen”.

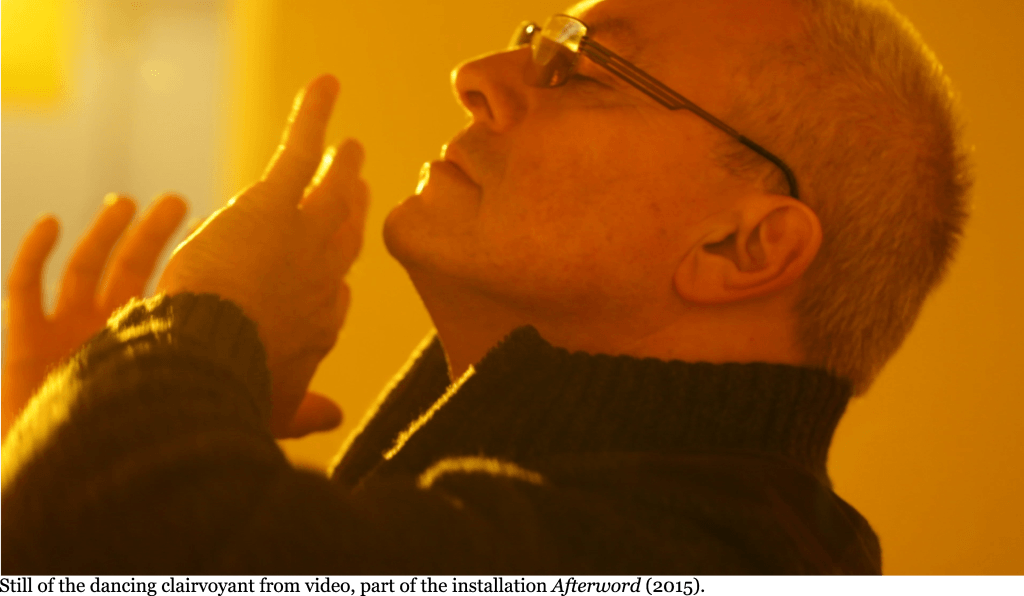

The installation also includes a video portraying a dancing clairvoyant used by Santillan to contact the diseased philosopher and ask him: “What was your dance like?” The resulting performance is the connection between the clairvoyant and the philosopher almost a century after his death through a fragment of paper taken directly from one of Nietzsche’s typed manuscripts (which is also presented in the installation).

Santillan’s artwork Afterword (2015) actually brings us back to the Deleuzian notion of the crystal image and the multilayered reality. That is to say, for Deleuze, the crystal image entails an interaction of the actual and the virtual. This result produces a multilayered apprehension of time and a multi-modal production of temporality by using the notion of smalls sparks which contains meaningful narratives. These sparks do not aim to comfort or replace the “real” narratives. Rather, they are aimed to last for a second and show the potential of how things could be without replacing the older system.[1]

Inspired by Santillan’s artwork, Adrastus Collection decided to include Afterword (2015) within its contemporary art heritage with the intention to continue re-symbolizing the images from the past and introduce them into the 21st century. In the near future, Adrastus Collection will engage into his most ambitious project at the moment: the creation of the “Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Contemporáneo Castilla y León – Colección Adrastus” in Arévalo, Spain. In order to hold permanently the best of the artistic creation of the 21st century, Adrastus Collection will recover the ruins of the first Jesuit School and multilayered it into a contemporary art museum. Just like the Deleuzian notion of crystal image, the restoration of the architectonic space will function as sparks intended to bring back the Jesuit School’s intellectual monumentality.

Oscar Santillan received an MFA degree in Sculpture from Virginia Common Wealth University, and has attended residencies at Fondazione Ratti in Italy, Delfina Foundation in the UK, Skowhegan and Seven Below, both in USA. His work has been displayed at the Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil in Mexico, the Havana Biennal in Cuba, The Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art in USA, Bonnefanten Museum in The Netherlands, in Guatemala Biennal, among other venues. His work is held in public and private collections internationally, including the Caldic Collection, Balanz Capital, Colección Franc Vila, Centraal Museum, Bieke and Tanguy van Quickenborne Collection, and most recently, Adrastus Collection.

[1] Van Den Akker, Robin. “My Work Is a Reaction to the Idea of the Latin American Artist. An Interview with Oscar Santillan.” Art Pulse Magazine 2015. Web. 29 Mar. 2016. <http://artpulsemagazine.com/my-work-is-a-reaction-to-the-idea-of-the-latin-american-artist-an-interview-with-oscar-santillan>.