Adrian Villar Rojas’s Theater of Disappearance

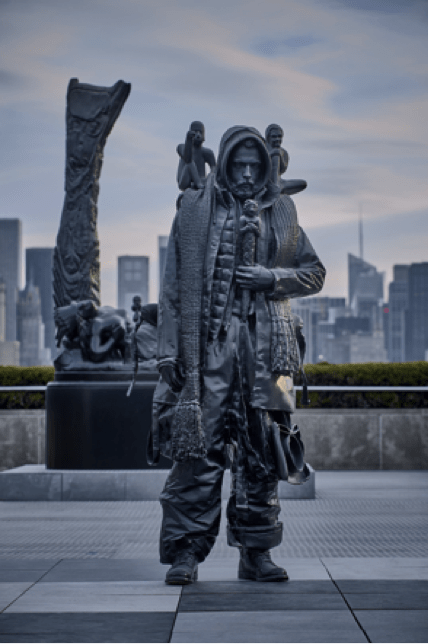

The Theater of Disappearance (14), 2017

Inert materials

Depending on how you look at it, Adrián Villar Rojas’s The Theater of Disappearance —The Met’s 2017 Roof Garden Commission— may, at first glance, seem like a surreal dreamscape, decked out with the decadent vestiges of a crazy party. Some of the sculptures are passed out on tables littered with broken wine glasses and plates, while others are found canoodling underneath other statues, or kissing near the terrace. If you linger on the rooftop at dusk, when the fog wraps around the skyscrapers, the sculptures begin to appear like a conjuration of ghosts haunting the Museum and watching over the city.

The Theater of Disappearance encompasses thousands of years of artistic production over several continents and cultures, and fuses them with facsimiles of contemporary human figures as well as furniture, animals, cutlery, and food. Each object—whether a 1,000-year-old decorative plate or a human hand—is rendered in the same black or white material and coated in a thin layer of dust.

Adrastus Collection is proud to present one of its most recent acquisitions: The Theater of Disappearance (14), marvelous sculpture which seeks to dialogue with the vision and division of The Met’s patrimony. An entire cartography of human culture seems to emerge from the Museum’s wings and rooms. Rather than a mirror of facts, the Museum becomes a version of them: America’s map of human activity on earth, a scale-model account of who we are and how we got here.

The Theater of Disappearance

Villar Rojas serves up uncanny hybrids, stirred together from objects in the Met’s collection. Severe hands and arms abound: one pair lifts an empty platter, another twists its fingers, and other ones are rocking. But there are plenty of other masks as well, hailing from Oceania, Japan and Africa. Horse heads, pharaoh heads and fragmented bits of skull consort with sheep horns, seals, coins, weapons and earthenware. The 37-year-old Argentine artist mingles them into wild cornucopias.

The installation of 16 black and white sculptures, The Theater of Disappearance looks like a freewheeling Bacchanalian fete. To unite the social and commercial aspects of the roof with his work, Villar Rojas has integrated each element into the conceit of a fantastical event. Decadent banquet tables occupy an oversize black-and-white checkerboard floor, punctuated by his exceptional sculptures and visitors become partygoers. The celebratory tone is fitting considering the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Roof Garden’s status as a summertime date destination where visitors drink cocktails and take in the impressive vista of Central Park.

But this installation is about more than just revelry. Villar Rojas dug deep into the Met’s collection to revive a forgotten part of its holdings: plaster casts and copies. “The Met’s history as an institution is a testimony to America’s path as a nation. Its doors opened in 1870 with a large collection of plaster casts of sculptural masterpieces,” Villar Rojas said in a statement. “By the mid-twentieth century, genuine artifacts had displaced the copies.” The resulting diorama, in which the public plays various parts in the larger performance of a party, constitutes a radical interpretation of the museum space.

The Met’s associate chief photographer Oi-Cheong Lee and its chief photographer Joseph Coscia scanning Haremhab.

In accepting the commission, the artist encountered a history of human culture that emerges from the Museum’s galleries. The installation is full of duplicity: it is both academic and whimsical, disruptive and atmospheric. Rojas refers to it as a Museum-wide scavenger hunt, one that boasts more than 100 replicated pieces handpicked from an array of sculpture representing several of The Met’s curatorial departments. Villar Rojas chose the objects he wanted to replicate for use as raw materials, and staff members from the Met’s imaging department were busy creating three-dimensional images to make that happen. They used two methods. The first was photogrammetry, a process born out of aerial and architectural mapping that can create a 3-D model from an array of images shot with a regular camera. The second process used the Met’s new laser scanner to collect millions of data points and then transpose them into a 3-D model. The replicas were either milled or 3D printed, and are made in urethane foam coated with matte industrial paint. At the end, this installation became a colossal historic task of investigating the museum’s collecting practice. In addition to selecting objects from across the Met’s 17 departments, the artist also scanned staff members and their families to create the human figures who populate the scene. (He did not spare himself: Villar Rojas’s own hand can be seen hovering above one sculpture. His fingers are in the shape of a rock n’ roll sign.)

Left: 3D Model of The Theater of Disappearance (10), 2017. Right: Final sculpture The Theater of Disappearance (10), 2017

Villar Rojas has stated that he aimed to destabilize the hierarchy of museums, an intent that is evident in the way he presented the sculptures. For example, in a mise-en-scène that seems to mimic the folkloric tale of a stork that delivers babies, a swaddled baby lies on a table next to a large bird that watches over it. The bird was originally made by the Senufo people in the Ivory Coast at some point in the 19th to mid-20th century.

Left: View of The Theater of Disappearance (5), 2017. Right: Bird (Sejen), 19th–mid-20th century.

Other treasures from the collection are harder to spot, having been divorced from their usual color and texture and kit-bashed together into alien arrangements and strange chimerical creatures. A master of manipulation, Villar Rojas has created an environment that is difficult to parse—only the most knowledgeable Met-lovers will be able to identify the origins of each piece.

Preoccupied with the presence and politics of art, Villar Rojas’s work elicits a sense of visual disturbance of time and space. Known for his large-scale installations, he deconstructs the status quo of every site, altering its environment to generate entirely new conditions for encountering his art. The concept of simulation provides a framework for Villar Rojas’s method of interpretation and his reenactment of objects.

The Theater of Disappearance could be the setting for an entirely new world, or the last party on earth, hundreds of years from now, featuring table centerpieces that look as if they were the petrified remains of humans performing everyday activities. It is a grand fiction of liberated objects being held, loved and touched, absorbing and re-presenting the imagery of Museum objects unconstrained by time and demarcations of culture. In probing the Museum’s role in framing historical truth, Villar Rojas aims to disrupt its traditional presentations to allow for the reactivation and a reinterpretation of art and human culture.

The Theater of Disappearance creates a rupture that points to the fact that history is edited, that it is moved and positioned and repositioned by human hands—in this case those of Villar Rojas. The artist shows that these works are imbued with a narrative that was chosen by curators and art historians, and attempts to release them from the standard narrative we assign to art history. The installation serves to subvert the narrative put forth by geographically divided curatorial departments with a new generation of sculptures, all of which are inspired by repeating patterns that respond to the fundamental human concerns– such as reproduction, the harvest, and the afterlife– that have remained constant over the past five thousand years. The charged proximities that come from this merging art and time, with an explicit contemporary human presence, evoke a playful but disarming response.

View of The Theater of Disappearance on the rooftop of The Metropolitan Museum of New York, 2017

Adrián Villar Rojas has been the recipient of numerous awards including The Zurich Art Prize at the Museum Haus Konstruktiv (2013), and the 9th Benesse Prize in the 54th Venice Biennial (2011). He has participated in various residences: SAM Art Projects, Paris, France (2011); Banff Centre Institute, Alberta, Canada (2010); La Residencia, Bogotá, Colombia (2010); and at the Panorama Brasileiras das Artes, Sao Paulo, Brazil (2009). His most important exhibitions include: Adrián Villar Rojas – Fantasma, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Sweden (2015); The Evolution of God, High Line at the Rail Yards, New York United States (2014); Adrián Villar Rojas – Films Before Revolution, Museum Haus Konstruktiv, Zürich, Zwitzerland (2013); Today We Reboot the Planet, Serpentine Sackler Gallery, London, United Kingdom (2013); Adrián Villar Rojas: La inocencia de los animales, Expo 1, MoMA PS1, New York, United States (2013); Return the world, dOCUMENTA (13), Kassel Germany (2012); Before my birth, Arts Brookfield with The New Museum triennial “The Ungovernables” and World Financial Center Plaza New York, USA (2012); El asesino de tu herencia (The Murderer of Your Heritage), 54th Venice Biennial, Argentinian pavilion, Venice, Italy (2011); Poems for Earthlings, SAM ART Projects, Jardin des Tuileries, Musée du Louvre Paris, France (2011). Moreover, his work has been included in group exhibitions at institutions such as The New Museum, New York, United States (2012); Serpentine Gallery, London, United Kingdom (2010); Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Germany (2010); CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, San Francisco, United States (2009); Sao Paulo Museum of Modern Art, São Paulo, Brazil (2009) among others.