The Nostalgic Faux-finish Pictorial Trip of Slawomir Elsner

Shadow-like figures, lonely places and left-behind objects are part of the realistic, albeit emotionally skewed representations of Slawomir Elsner’s world. The ominous visual language of this artist leaves many things unsaid, kept secret and hidden in his paintings, which reveal their meaning through subtle details. While far from being conceptual or abstract, Slawomir Elsner nevertheless manages –through figurative paintings based on photographic images- to play with the expectations and visual habits of the spectator, as well as with one’s imagination and willingness to perceive new things.

His hyperrealistic style conveys his personal reinterpretation of mundane scenes of daily life, creating new meanings and inviting the viewer to multiple interpretations. The carefully selected stills used by Elsner in Grandpa’s House series, are inspired by a group of photographs taken by the artist in 2000. Empty chairs and televisions fill the inhabited spaces, as in Grandpa’s House (Room4). The sense of absence is echoed in this series depicting rooms in which details are obscured by dark shadows, leaving the viewer with an unsettling sense of abandonment.

The bank of images that serves as inspiration for Elsner’s artworks might come from external resources such as illustrations, magazines and even self-taken photographs, mostly presented in series formats. In the Panorama series, Elsner uses oil paintings to reproduce images from the low-budget Silesian illustrated weekly magazine, of the same title, that was published in 1976. In order to commemorate his 30th birthday, Elsner’s father gave him the Panorama volume from the month and year when he was born. Several dozen of oil paintings “translate” the 30-year-old advertisements, news reports and fashion layouts into contemporaneity. The artist accurately painted each page of the magazine, not only rigorously capturing the images, but also recreating scrupulously the physicality of the paper, including its deterioration, its yellowish color and the printing’s aging. This attention to detail in Elsner’s production can be seen in artworks like Panorama (04), Panorama 28, Panorama 64 and Panorama 65, which are currently representative artworks from this artist in the Adrastus Collection.

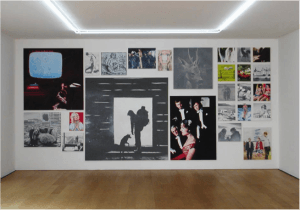

Panorama

The result of the Panorama series is an evocative painting montage that feels more like a family scrapbook than reproductions of pictures from a magazine. This is due in part to having eleven of the images displayed as disparately proportioned works positioned barely an inch apart. The overall impression of a collaged, composite mass, starts as a personal anecdote, but in the end becomes a visual documentary on 1976 Poland.

By retrieving drawings, paintings, and photographs, Elsner achieves an aesthetic appropriation almost unrecognizable from the original image. For example, in the Old Street series, which is inspired by a set of photographs taken by himself, Elsner takes the disheartening familiarity of homelessness and transforms it into a personal statement. His form of representation, as is seen in Old Street 11, stretches the tension between objective photographic reality and subjective visual memory. That is to say, he depicts recognizable scenes from real life, but distorts them into private, and sometimes deeply emotional, compositions.

The Polish artist born in 1976 often recurs to press photography, copying archive images and enlarging his drawings to a bigger scale. This method intensifies the sensation of antiquity and seduces the viewer with sheer size; the bigger something is in a newspaper, the more important it is. In Erste Dame der polnischen Museen the artist makes a hazy, ghostly and disproportioned representation of a photographic picture with historical relevance. The relevance of the scene is such to the artist that the artwork actually measures 170 x 180 cm.

Elsner’s work can be seen in major international collections and museums, including the Museum der Moderne in Salzburg, Austria, the Folkwang Museum in Essen, Germany and, most recently, in the Adrastus Collection.