Slowly Abandon Yourself to Rosa Barba’s Sensation

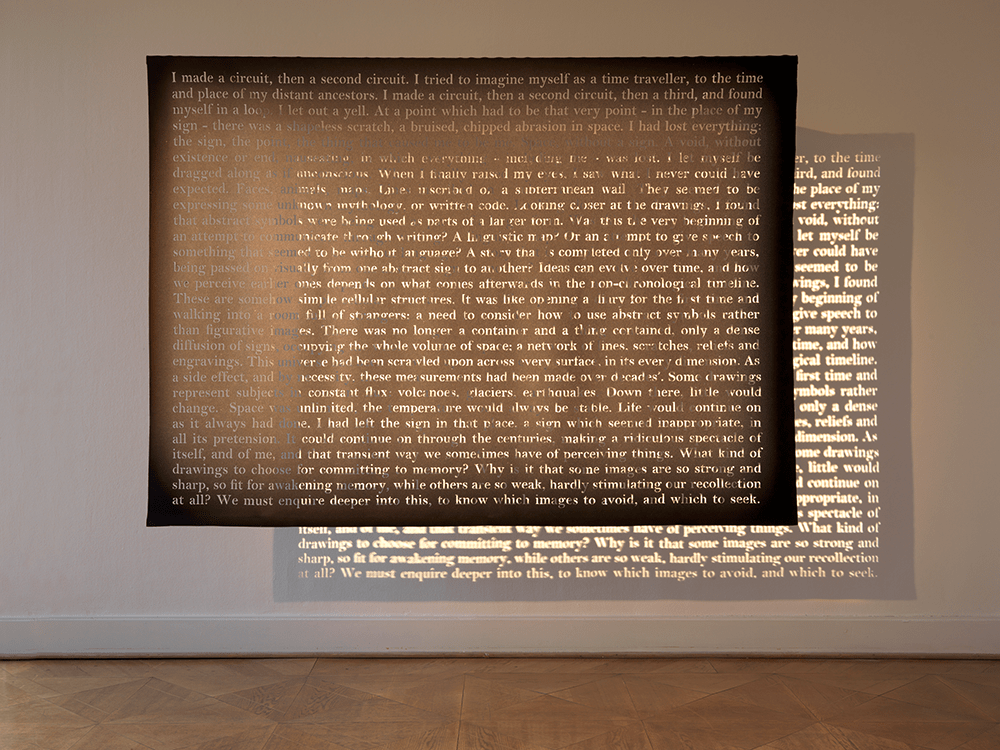

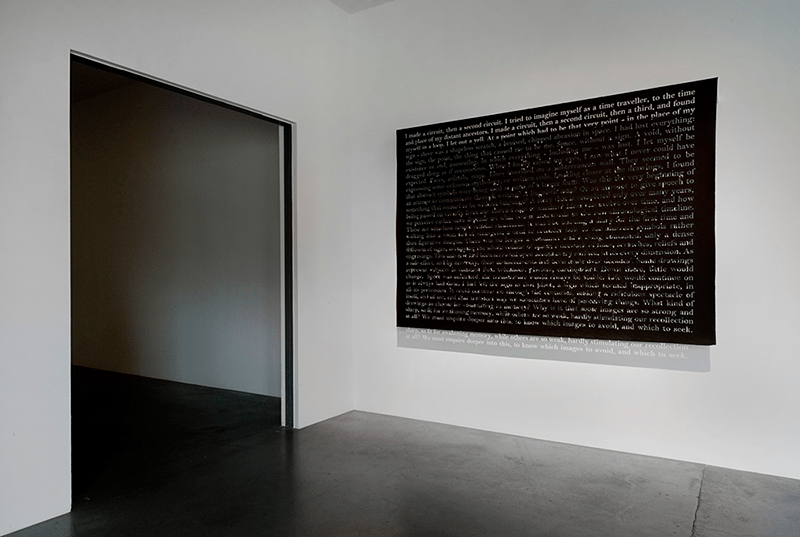

Cutout text on felt 70 6/7 x 94 1/2 in. (180 x 240 cm.)

I made a circuit, then a second circuit, I tried to imagine myself as a time traveler, to the time and place of my distant ancestors. I made a circuit, then a second circuit, then a third, and found myself in a loop. I let out a yell. At a point which had to be that very point – in the place of my sign – there was a shapeless scratch, a bruised, chipped, abrasion in space, I had lost everything: the sign, the point, the thing that caused me to be me. Space, without a sign. A void, without existence or end, nauseating, in which everything – including me – was lost. I let myself be dragged along as if unconscious. When I finally raised my eyes, I saw what I never could have expected. Faces, animals, maps, lines, inscribed on a subterranean wall. They seemed to be expressing some unknown mythology, or written code. Looking closer at the drawings, I found that abstract symbols were being used as parts of a larger form. Was this the very beginning of an attempt to communicate through writing? A linguistic map? Or an attempt to give speech to something that seemed to be without language? A story that is completed only over many years being passed on visually from one abstract sign to another? Ideas can evolve over time, and how we perceive earlier ones depends on what comes afterwards in the nonchronological timeline. These are somehow simple cellular structures. It was like opening a diary for the first time and walking into a room full of strangers; a need to consider how to use abstract symbols rather than figurative images. There was no longer a container and a thing contained, only a dense diffusion of signs, occupying the whole volume of space, a network of lines, scratches, reliefs and engravings. This universe had been scrawled upon across every surface, in its every dimension. As a side effect, and by necessity, these measurements had been made over decades. Some drawings represent subjects in constant flux: volcanoes, glaciers, earthquakes. Down there, little would change. Space was unlimited, the temperature would always be stable. Life would continue as it always had done. I had left the sign in that place, a sign which seemed inappropriate, in all its pretension. It could continue on through the centuries, making a ridiculous spectacle of itself, and of me, and that transient way we sometimes have of perceiving things. What kind of drawings to choose for committing to memory? Why is it that some images are so strong and sharp, so fit for awakening memory, while others are so weak, hardly stimulating our recollection at all? We must enquire deeper into this, to know which images to avoid, and which to seek.

Time is inextricably linked with the idea of movement in Barba’s installations. In them the old-fashioned projectors refer us to the past but their performance makes sense only in the present, when the spools of transparent celluloid are in motion. In the absence of filmic or photographic images, it is the feeling of suspended time that remains, or in Barba’s words, “slowly we abandon ourselves to the sensation”.[1]

It may seem superfluous to assert that Rosa Barba’s practice is exclusively engaged with issues of temporality: her primary medium is film and all her other forms relate in some way to filmic practices, history and its genres. But it is not the literal fact of working with a time-based medium that is the focus of I Made a Circuit, Then a Second Circuit (2010); rather, the ways in which temporality is spatialised and visualized by different kinds of works that fold multiple registers of time and space into each other.

Rosa Barba was born in Agrigento in 1972 and grew up in Germany where she studied at the Academy of Media Arts in Cologne followed by a residency at the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam. She currently lives and works in Berlin. Barba has exhibited extensively internationally, including solo shows at the Museo Nazionale delle Arti XXI secolo, Rome (2014), CAC, Center of Contemporary Art, Vilnius (2014), Turner Contemporary in Margate (2013), Cornerhouse in Manchester (2013), MUSAC in Castilla y Leon (2013), Bergen Kunsthall (2013), Kunsthaus Zürich (2012), Jeu de Paume, Paris, (2012), Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, Fondazione Galleria Civica, Trient (2011), MART, Rovereto (2011), Kunstverein Braunschweig (2011) and Tate Modern, London (2010). She participated at the 52th (2007) and 53rd (2009) Biennial in Venice, the 2nd Thessaloniki Biennial of Contemporary Art (2009), the Liverpool Biennial (2010), and the Biennial of Sydney (2014).

[1] Cámara, Cristina. “Rosa Barba.” Tate Museum. 2010. Web. 13 Sept. 2016.http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/level-2-gallery-rosa-barba/rosa-barba-cristina-camara